Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot, (Hebrew: יהודה איש־קריות, Yehuda, Yəhûḏāh ʾΚ-qəriyyôṯ) was, according to the New Testament, one of the twelve original apostles of Jesus. Of the twelve, he alone is reported to have kept a "money bag" (Greek: γλωσσόκομον),[1] but he is best known for his role in betraying Jesus into the hands of the chief priests.[2]

Contents |

Etymology

In the Greek New Testament, Judas is called Ιούδας Ισκάριωθ (Ioúdas Iskáriōth) and Ισκαριώτης (Iskariṓtēs). "Judas" (spelled "Ioudas" in ancient Greek and "Iudas" in Latin, pronounced ˈyudas' in both) is the Greek form of the common name Judah (יהודה, Yehûdâh, Hebrew for "God is praised"). The same Greek spelling underlies other names in the New Testament that are traditionally rendered differently in English: Judah and Jude.

The precise significance of "Iscariot," however, is uncertain. There are two major theories on its etymology:

- The most likely explanation derives Iscariot from Hebrew איש־קריות, Κ-Qrîyôth, or "man of Kerioth." The Gospel of John refers to Judas as "son of Simon Iscariot",[3] implying it was not Judas, but his father, who came from there.[4] Some speculate that Kerioth refers to a region in Judea, but it is also the name of two known Judean towns.[5]

- A second theory is "Iscariot" identifies Judas as a member of the sicarii.[6] These were a cadre of assassins among Jewish rebels intent on driving the Romans out of Judea. However, many historians maintain the sicarii only arose in the 40s or 50s of the first century, in which case Judas could not have been a member.[7]

Biblical narrative

Judas is mentioned in the synoptic gospels, the Gospel of John and at the beginning of Acts of the Apostles.

Mark states that the chief priests were looking for a "sly" way to arrest Jesus. They decided not to do so during the feast because they were afraid that the people would riot; instead, they chose the night before the feast to arrest him. In the Gospel of Luke, Satan enters Judas at this time.[8]

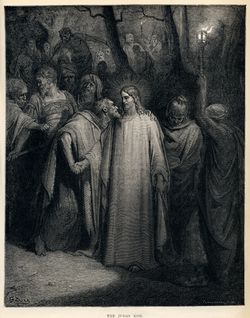

According to the account given in the Gospel of John, Judas carried the disciples' money bag[9] and betrayed Jesus for a bribe of "thirty pieces of silver"[10] by identifying him with a kiss—"the kiss of Judas"—to arresting soldiers of the High Priest Caiaphas, who then turned Jesus over to Pontius Pilate's soldiers.

Death

There are two different references to the remainder of Judas' life in the modern Biblical canon.

Other references exist outside of the modern Biblical canon :

- The Gospel of Matthew says that, Judas returned the money to the priests and committed suicide by hanging himself. The priests used it to buy the potter's field[11] . The Gospel account[Matthew 27:9-10] presents this as a fulfilment of prophecy.

- The Acts of the Apostles says that Judas used the money to buy a field, but fell down headfirst, and burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out. This field is called Akeldama or Field Of Blood.[12]

- The "Gospel of Judas" says that the other eleven disciples stoned him to death after they found out about the betrayal. [13]

Another account was preserved by the early Christian leader, Papias: "Judas walked about in this world a sad example of impiety; for his body having swollen to such an extent that he could not pass where a chariot could pass easily, he was crushed by the chariot, so that his bowels gushed out."[14]

The existence of conflicting accounts of the death of Judas caused problems for traditional scholars who saw them as threatening the reliability of Scripture.[15] This problem was one of the points that caused C. S. Lewis, for example, to reject the view "that every statement in Scripture must be historical truth".[16] Various attempts at harmonization have been suggested, such as that of Augustine that Judas hanged himself in the field, and afterwards the rope snapped, and his body burst open on the ground,[15][17] or that the accounts of Acts and Matthew refer to two different transactions.[18]

Modern scholars tend to reject these approaches[19][20][21] stating that the Matthew account is a midrashic exposition that allows the author to present the event as a fulfillment of prophetic passages from the Old Testament. They argue that the author adds imaginative details such as the thirty pieces of silver, and the fact that Judas hangs himself, to an earlier tradition about Judas's death.[22]

Matthew's reference to the death as fulfilment of a prophecy "spoken through Jeremiah the prophet" has caused some controversy, since it clearly paraphrases a story from the Book of Zechariah([Zechariah 11:12-13]) which refers to the return of a payment of thirty pieces of silver.[23] Many writers, such as Augustine, Jerome, and John Calvin concluded that this was an obvious error.[24] However, some modern writers have suggested that the Gospel writer may also have had a passage from Jeremiah in mind,[25] such as chapters 18([Jeremiah 18:1–4]) and 19([Jeremiah 19:1–13]), which refers to a potter's jar and a burial place, and chapter 32[Jeremiah 32:6-15] which refers to a burial place and an earthenware jar.[26]

Theology

Betrayal of Jesus

There are several explanations of why Judas betrayed Jesus.[27] A common explanation is that Judas betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14-16). One of Judas's main weaknesses seemed to be money (John 12:4-6). Another possible reason is that Judas expected Jesus to overthrow Roman rule of Israel. In this view, Judas is a disillusioned disciple betraying Jesus not so much because he loved money, but because he loved his country and thought Jesus had failed it.[28] According to Luke 22:3-6 and John 13:27, Satan entered into him and called him to do it.

The Gospels suggests that Jesus both foresaw (John 6:64, Matthew 26:25) and allowed Judas's betrayal (John 13:27-28)[29]. An explanation is that Jesus allowed the betrayal because it would allow God's plan to be fulfilled.[30] In April 2006, a Coptic papyrus manuscript titled the Gospel of Judas dating back to 200 AD, was translated into modern language, suggests that Jesus may have asked Judas to betray him,[31] although some scholars question the translation.[32][33]

Origen knew of a tradition according to which the greater circle of disciples betrayed Jesus, but does not attribute this to Judas in particular, and Origen did not deem Judas to be thoroughly corrupt (Matt., tract. xxxv).

Judas is also the subject of many philosophical writings, including The Problem of Natural Evil by Bertrand Russell and "Three Versions of Judas", a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. They both allege various problematic ideological contradictions with the discrepancy between Judas's actions and his eternal punishment. John S. Feinberg argues that if Jesus foresees Judas's betrayal, then the betrayal is not an act of free will[34], and therefore should not be punishable. Conversely, it is argued that just because the betrayal was foretold, it does not prevent Judas from exercising his own free will in this matter.[35] Other scholars argue that Judas acted in obedience to God's will.[36] The gospels suggest that Judas is apparently bound up with the fulfillment of God's purposes(John 13:18, John 17:12, Matthew 26:23-25, Luke 22:21-22, Matt 27:9-10, Acts 1:16, Acts 1:20)[29], yet woe is upon him, and he would have been better unborn(Matthew 26:23-25). The difficulty inherent in the saying is its paradoxicality - if Judas had not been born, the Son of Man will apparently no longer go "as it is written of him". The consequence of this apologetic approach is that Judas's actions come to be seen as necessary and unavoidable, yet leading to condemnation.[37]

Erasmus believed that Judas was free to change his intention, but Martin Luther argued in rebuttal that Judas's will was immutable. John Calvin states that Judas was predestined to damnation, but writes on the question of Judas's guilt: "...surely in Judas betrayal, it will be no more right, because God himself willed that his son be delivered up and delivered him up to death, to ascribe the guilt of the crime to God than to transfer the credit for redemption to Judas."[38]

It has been speculated that Judas's damnation, which seems to be possible from the Gospels' text, may not actually stem from his betrayal of Christ, but from the despair which caused him to subsequently commit suicide.[39] This position is not without its problems since Judas was already damned by Jesus even before he committed suicide (see John 17:12), but it does avoid the paradox of Judas's predestined act setting in motion both the salvation of all mankind and his own damnation. The damnation of Judas is not a universal conclusion, and some have argued that there is no indication that Judas was condemned with eternal punishment.[40] Adam Clarke writes: "he[Judas] committed a heinous act of sin...but he repented(Matthew 27:3-5) and did what he could to undo his wicked act: he had committed the sin unto death, i.e. a sin that involves the death of the body; but who can say, (if mercy was offered to Christ's murderers?(Luke 23:34)...) that the same mercy could not be extended to wretched Judas?..."[41]

Modern interpretations

Most Christians still consider Judas a traitor. Indeed the term Judas has entered many languages as a synonym for betrayer.

Some scholars[42] have embraced the alternative notion that Judas was merely the negotiator in a prearranged prisoner exchange (following the money-changer riot in the Temple) that gave Jesus to the Roman authorities by mutual agreement, and that Judas's later portrayal as "traitor" was a historical distortion.

In his book The Passover Plot the British theologian Hugh J. Schonfield argued that the crucifixion of Christ was a conscious re-enactment of Biblical prophecy and Judas acted with Jesus' full knowledge and consent in "betraying" his master to the authorities.

Theologian Aaron Saari contends in his work The Many Deaths of Judas Iscariot that Judas Iscariot was the literary invention of the Markan community. As Judas does not appear in the Epistles of Paul, nor in the Q Gospel, Saari argues that the language indicates a split between Pauline Christians, who saw no reason for the establishment of an organized Church, and the followers of Peter. Saari contends that the denigration of Judas in Matthew and Luke-Acts has a direct correlation to the elevation of Peter.[43]

Mark 16:14 and Luke 24:33 state that following his resurrection Jesus appeared to "the eleven." Who was missing? After all that had transpired one would just naturally think it was Judas. Apparently not, because in John 20:24 we learn that the one missing was Thomas. Therefore the eleven had to include Judas. To further confuse things, Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15:5 that following his resurrection Jesus was seen by “the twelve.” This had to include Judas because it wasn't until after the ascension, some forty days after the resurrection (Acts 1:3), that another person, Matthias, was voted in to replace Judas (Acts 1:26). So, apparently Judas neither committed suicide nor died by accident. In Acts 1:25 we are told that Judas "turned aside to go to his own place."

Another clue confirming the absence of the Judas story in the earliest Christian documents occurs in Matthew 19:28 and Luke 22:28-30. Here Jesus tells his disciples that they will “sit on the twelve thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel.” No exception is made for Judas even though Jesus was aware of his impending act of betrayal. The answer may lie in the fact that the source of these verses could be the hypothetical Q document (QS 62). Q is thought to predate the gospels and would be one of the earliest Christian documents. Given that possibility, the betrayal story could have been invented by the writer of Mark.[44][45][46]

The book The Sins of the Scripture, by John Shelby Spong, investigates the possibility that early Christians compiled the Judas story from three Old Testament Jewish betrayal stories. He writes, "...the act of betrayal by a member of the twelve disciples is not found in the earliest Christian writings. Judas is first placed into the Christian story by Gospel of Mark (3:19), who wrote in the early years of the eighth decade of the Common Era". He points out that some of Gospels, after the Crucifixion, refer to the number of Disciples as "Twelve", as if Judas were still among them. He compares the three conflicting descriptions of Judas's death - hanging, leaping into a pit, and disemboweling, with three Old Testament betrayals followed by similar suicides.

Spong's conclusion is that early Bible authors, after the First Jewish-Roman War, sought to distance themselves from Rome's enemies. They augmented the Gospels with a story of a disciple, personified in Judas as the Jewish state, who either betrayed or handed-over Jesus to his Roman crucifiers. Spong identifies this augmentation with the origin of modern Anti-Semitism.

Jewish scholar Hyam Maccoby, espousing a purely mythological view of Jesus, suggests that in the New Testament, the name "Judas" was constructed as an attack on the Judaeans or on the Judaean religious establishment held responsible for executing Christ.[47] The English word "Jew" is derived from the Latin Iudaeus, which, like the Greek Ιουδαίος (Ioudaios), could also mean "Judaean".

"Judas The Beloved Disciple Remembered" by William E. McClintic portrays Judas in a positive light. McClintic not only presents Judas as the "beloved disciple", but also as a scribe and author of the "Q" document, the "Apostles Creed" and true writer of the "John Gospel". McClintic presents Judas as the source of most of the stories about Jesus in the Gospels from the birth of Jesus, his education, his teachings and ministry to the trial, Crucifixion and Resurrection.

Role in apocrypha

Judas has been a figure of great interest to esoteric groups, such as many Gnostic sects. Irenaeus records the beliefs of one Gnostic sect, the Cainites, who believed that Judas was an instrument of the Sophia, Divine Wisdom, thus earning the hatred of the Demiurge. In the Hebrew bible, the book of Zechariah, the one who casts thirty pieces of silver, as Judas does in the Gospels, is a servant of God. His betrayal of Jesus thus was a victory over the materialist world. The Cainites later split into two groups, disagreeing over the ultimate significance of Jesus in their cosmology.

Gospel of Judas

During the 1970s, a Coptic papyrus codex (book) was discovered near Beni Masah, Egypt which appeared to be a third- or fourth-century-AD copy of a second-century original,[48][49] describing the story of Jesus's death from the viewpoint of Judas. At its conclusion, the text identifies itself as "the Gospel of Judas" (Euangelion Ioudas).

The discovery was given dramatic international exposure in April 2006 when the US National Geographic magazine (for its May edition) published a feature article entitled The Gospel of Judas with images of the fragile codex and analytical commentary by relevant experts and interested observers (but not a comprehensive translation). The article's introduction stated: "An ancient text lost for 1,700 years says Christ's betrayer was his truest disciple".[50] The article points to some evidence that the original document was extant in the second century: "Around A.D. 180, Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon in what was then Roman Gaul, wrote a massive treatise called Against Heresies [in which he attacked] a 'fictitious history,' which 'they style the Gospel of Judas.'"[51]

Before the magazine's edition was circulated, other news media gave exposure to the story, abridging and selectively reporting it.[31]

In December 2007, a New York Times op-ed article by April DeConick asserted that the National Geographic's translation is badly flawed: For example, in one instance the National Geographic transcription refers to Judas as a "daimon", which the society’s experts have translated as "spirit". However, the universally accepted word for "spirit" is "pneuma" — in Gnostic literature "daimon" is always taken to mean "demon".[52] The National Geographic Society responded that 'Virtually all issues April D. DeConick raises about translation choices are addressed in footnotes in both the popular and critical editions'.[53] In a later review of the issues and relevant publications, critic Joan Acocella questioned whether ulterior intentions had not begun to supersede historical analysis, e.g., whether publication of The Gospel of Judas could be an attempt to roll back ancient antisemitic imputations. She concluded that the ongoing clash between scriptural fundamentalism and attempts at revision were childish because of the unreliability of the sources. Therefore, she argued, "People interpret, and cheat. The answer is not to fix the Bible but to fix ourselves".[54] Other scholars such as Louis Painchaud (Laval University, Quebec City) and André Gagné (Concordia University, Montreal)[32] have also questioned the initial translation and interpretation of the Gospel of Judas by the National Geographic team of experts.

Gospel of Barnabas

According to medieval copies of the Gospel of Barnabas, it was Judas, not Jesus, who was crucified on the cross. It is mentioned in this work that Judas's appearance was transformed to that of Jesus', when the former, out of betrayal, led the Roman soldiers to arrest Jesus who by then was ascended to the heaven. This transformation of appearance was so identical that the masses, followers of Christ, and even the Mother of Jesus, Mary, initially thought that the one arrested and crucified was Jesus himself. The Gospel then mentions that after three days since burial, Judas's body was stolen from his grave, and then the rumors spread of Jesus being risen from the dead. When Jesus was informed in the third heaven about what happened, he prayed to God to be sent back to the earth, and so he descended and gathered his mother, disciples, and followers and mentioned to them the truth of what happened, and having said this he ascended back to the heavens, and will come back at the end of times as a just king.

Representations and symbolism

The term Judas has entered many languages as a synonym for betrayer, and Judas has become the archetype of the traitor in Western art and literature. Judas is given some role in virtually all literature telling the Passion story, and appears in a number of modern novels and movies.

In the Eastern Orthodox hymns of Holy Wednesday (the Wednesday before Pascha), Judas is contrasted with the woman who anointed Jesus with expensive perfume and washed his feet with her tears. According to the Gospel of John, Judas protested at this apparent extravagance, suggesting that the money spent on it should have been given to the poor. After this, Judas went to the chief priests and offered to betray Jesus for money. The hymns of Holy Wednesday contrast these two figures, encouraging believers to avoid the example of the fallen disciple and instead to imitate Mary's example of repentance. Also, Wednesday is observed as a day of fasting from meat, dairy products, and olive oil throughout the year in memory of the betrayal of Judas. The prayers of preparation for receiving the Eucharist also make mention of Judas's betrayal: "I will not reveal your mysteries to your enemies, neither like Judas will I betray you with a kiss, but like the thief on the cross I will confess you."

Judas Iscariot is often represented with red hair in Spanish culture [55] [56] [57] and William Shakespeare [58][57], associated to a negative stereotype against redheads.

Art and literature

Judas has become the archetype of the betrayer in Western culture, with some role in virtually all literature telling the Passion story.

- In Dante's Inferno, he is condemned to the lowest circle of Hell, where he is one of three sinners deemed evil enough that they are doomed to be chewed for eternity in the mouths of the triple-headed Satan. (The others are Brutus and Cassius, who conspired against and assassinated Julius Caesar.)

- Judas is the subject of one of the oldest surviving English ballads, dating from the 13th century, Judas, in which the blame for the betrayal of Christ is placed on his sister.

- Edward Elgar's oratorio, The Apostles, depicts Judas as wanting to force Jesus to declare his divinity and establish the kingdom on earth. Eventually he succumbs to the sin of despair.

- In Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita, Judas is paid by the high priest of Judaea to testify against Jesus, who had been inciting trouble among the people of Jerusalem. After authorizing the crucifixion, Pilate suffers an agony of regret and turns his anger on Judas, ordering him assassinated. The story-within-a-story appears as a counter-revolutionary novel in the context of Moscow in the 1920s-1930s.

- Michael Moorcock's novel Behold the Man offers an alternative, sympathetic portrayal of Judas. In the book, Karl Glogauer, the time traveler from the 20th Century who takes on the role of Christ, asks a reluctant Judas to betray him in order to fulfill the biblical account of the crucifixion.

- In C. K. Stead's novel My Name Was Judas, Judas, who was then known as Idas of Sidon, recounts the story of Jesus and recalled by him some forty years later. Judas recalls his childhood friendship with Jesus, their schooldays, their families, their journeys with the disciples and their dealings with the powers of Rome and the Temple.

- Three Versions of Judas (original Spanish title: "Tres versiones de Judas") is a short story by Argentine writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges. It was included in Borges' anthology, Ficciones, published in 1944. It is written in form of a scholarly article and appears on the surface to be a well researched critical analysis.

- In The Greatest Story Ever Told, Judas (played by David McCallum) appears like the 'Passion' Judas, yet also adds the words, 'I don't want the money'.

- In Martin Scorsese's film The Last Temptation of Christ, based on the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, Judas Iscariot's only motivation in betraying Jesus to the Romans was to help him, as Jesus' closest friend, through doing what no other disciple could bring himself to do. It shows Judas obeying Jesus' covert request to help him fulfill his destiny to die on the cross, making Judas the catalyst for the event later interpreted as bringing about humanity's salvation. This view of Judas Iscariot is reflected in the recently discovered Gospel of Judas.

- In Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, Judas (played by Luca Lionello) is shown to be extremely remorseful and haunted by guilt about betraying Jesus. He later pleads to Caiaphas to let him go. Tortured by devils, his grief eventually becomes too much and he hangs himself on a tree.

- In Tim Rice's and Andrew Lloyd Webber's theatrical production and film, Jesus Christ Superstar, Judas (played on the original concept album by Murray Head, on Broadway by Ben Vereen, Patrick Jude and Tony Vincent and on film by Carl Anderson and Jérôme Pradon) is betrayed as a tragic figure who, disillusioned by what he sees as Jesus' increasingly religious (rather than social) message and disturbed by Jesus's proclamation of divinity, turns Jesus over to the Romans because he fears violent reprisal from the latter.

- In The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, a critically acclaimed play by Stephen Adly Guirgis, Judas is given a trial in Purgatory.

- In the film Dracula 2000 (2000) and its sequels Dracula II: Ascension (2003) and Dracula III: Legacy (2005), the character of Count Dracula is revealed to be Judas Iscariot.

- In the non-fiction book The Flight of the Feathered Serpent (1953) by Armando Cosani, Judas reveals that he was asked secretly by Jesus to betray him, and in doing so, fulfilled a divine role and plan. This account correlates precisely with the Gospel of Judas which surfaced 53 years after the publication of this book.

- In James P. Blaylock's book The Last Coin, in modern times, Jules Pennyman attempts to gather the thirty ancient silver coins paid to Judas in order to command the magic collectively contained within. These coins, though, must, for the sake of the world, be kept separated.[59]

- Iscariot is a fictional organization from the manga series Hellsing. The Iscariot Organization, named after Judas Iscariot, is a top-secret wing of the Vatican charged with the active pursuit and extermination of demons (such as vampires) and heretics. The Iscariot 'paladins' are the elite fighting force of the Iscariot Organization

- In the album Death Magnetic, by Metallica "The Judas Kiss" is one of the songs.

- Judas Iscariot is a black metal band from Illinois, USA[60]

- The Lamb Of God song 'Omerta' is about Judas Iscariot, as evidenced by the lines "This id, what has been wrought for thirty pieces of silver; the tongues of men and angels bought by a beloved betrayer," and "St. Peter greets with empty eyes and turns to lock the gate".

- In the video game Dante's Inferno, Judas coins can be collected in order to acquire more experience. Also, there are trophies/achievements such as "Betrayed by a Kiss" and "Well done Judas" depending upon the amount of coins that have been collected.

- In the anime series Demon Lord Dante by Go Nagai, the character Dante transferred his human body to Judas Iscariot and his soul to the protagonist Ryo Utsugi (who at first believed Dante was actually Judas Iscariot) after he escaped from Sodom and Gomorrah when the two cities were destroyed by God and his demons as punishment for Satan refusing to sacrifice the human population to God's desire of having a human body.

- The Leon Rosselson song "Stand Up for Judas" presents Judas in a positive light, as a revolutionary who wanted justice in this world, not the next. Jesus, on the other hand, is presented as a "conjurer", working miracles and promising happiness in the next world, thus encouraging people to accept their lot in this world. The chorus of the song is "So stand up, stand up for Judas and the cause that Judas served/It was Jesus who betrayed the poor with his word."

References

- ↑ John 12:6, John 13:29

- ↑ Matthew 26:14, Matthew 26:47, Mark 14:10, Mark 14:42, Luke 22:1, Luke 22:47, John 13:18, John 18:1

- ↑ John 6:71 and John 13:26

- ↑ Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Eerdmans (2006), p. 106.

- ↑ New English Translation Bible, n. 11 in Matthew 11.

- ↑ Bastiaan van Iersel, Mark: A Reader-Response Commentary, Continuum International (1998), p. 167.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. (1994). The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels v.1 pp. 688-92. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-49448-3; Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus (2001). v. 3, p. 210. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0385469934.

- ↑ "BibleGateway.com - Passage Lookup: Luke 22:3". BibleGateway. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke%2022:3&version=31. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ↑ John 12:6

- ↑ Matthew 26:14

- ↑ (Greek, ton agron tou kerameōs, τὸν αγρὸν τοῦ κεραμέως)

- ↑ Acts 1:18.

- ↑ Judas Iscariot

- ↑ (Papias Fragment 3, 1742-1744).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Zwiep, Arie W. Judas and the choice of Matthias: a study on context and concern of Acts 1:15-26. p. 109.

- ↑ letter to Clyde S. Kilby, 7 May 1959, quoted in Michael J. Christensen, C. S. Lewis on Scripture, Abingdon, 1979, Appendix A.

- ↑ "Easton’s Bible Dictionary: Judas". christnotes.org. http://www.christnotes.org/dictionary.php?dict=ebd&q=Judas. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ "The purchase of "the potter's field", Appendix 161 of the Companion Bible". http://www.levendwater.org/companion/append161.html. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, p. 114.

- ↑ Charles Talbert, Reading Acts: A Literary and Theological Commentary, Smyth & Helwys (2005) p. 15.

- ↑ Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Eerdmans (2004), p. 703.

- ↑ Reed, David A. (2005). ""Saving Judas"—A social Scientific Approach to Judas’s Suicide in Matthew 27:3–10" (PDF). Biblical Theology Bulletin. http://academic.shu.edu/btb/vol35/06Reed.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Vincent P. Branick, Understanding the New Testament and Its Message, (Paulist Press, 1998), pp. 126-128.

- ↑ Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary (Eerdmans, 2004), p. 710; Augustine, cited in the Catena Aurea: "It might be then, that the name Hieremias occurred to the mind of Matthew as he wrote, instead of the name Zacharias, as so often happens" [1]; Jerome, Epistolae 57.7: "This passage is not found in Jeremiah at all but in Zechariah, in quite different words and an altogether different order" [2]; John Calvin, Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark and Luke, 3:177: "The passage itself plainly shows that the name of Jeremiah has been put down by mistake, instead of Zechariah, for in Jeremiah we find nothing of this sort, nor any thing that even approaches to it." [3].

- ↑ Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1985), pp. 107-108; Anthony Cane, The Place of Judas Iscariot in Christology (Ashgate Publishing, 2005), p. 50.

- ↑ See also Maarten JJ Menken, 'The Old Testament Quotation in Matthew 27,9-10', Biblica 83 (2002): 9-10.

- ↑ Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight, I. Howard Marshall (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. InterVaristy Press. p. 406. ISBN 9780830817771.

- ↑ Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight, I. Howard Marshall (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. InterVaristy Press. p. 407. ISBN 9780830817771.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Judas and the choice of Matthias: a study on context and concern of Acts 1:15-26, Arie W. Zwiep

- ↑ Did Judas betray Jesus Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, April 2006

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Associated Press, "Ancient Manuscript Suggests Jesus Asked Judas to Betray Him," Fox News Thursday, 6 April 2006.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 André Gagné, "A Critical Note on the Meaning of APOPHASIS in Gospel of Judas 33:1." Laval théologique et philosophique 63 (2007): 377-83.

- ↑ Deconick, April D. (December 1, 2007). "Gospel Truth". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/01/opinion/01deconink.html?_r=1&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ John S. Feinberg, David Basinger (2001). Predestination & free will: four views of divine sovereignty & human freedom. Kregel Publications. p. 91. ISBN 9780825434891.

- ↑ John Phillips (1986). Exploring the gospel of John: an expository commentary. InterVaristy Press. p. 254. ISBN 9780877845676.

- ↑ Authenticating the activities of Jesus, Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans

- ↑ The place of Judas Iscariot in christology, Anthony Cane

- ↑ A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature, David L. Jeffrey

- ↑ A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature, David L. Jeffrey

- ↑ http://www.tentmaker.org/Dew/Dew3/D3-JudasIscariot.html

- ↑ The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ: the text ... Volume 1, Adam Clarke

- ↑ Dirk Grützmacher : The "Betrayal" of Judas Iscariot : a study into the origins of Christianity and post-temple Judaism, Edinburgh 1998 (Thesis (M.Phil) --University of Edinburgh, 1999).

- ↑ Saari, Aaron Maurice. The Many Deaths of Judas Iscariot: A Meditation on Suicide London: Routledge, 2006.

- ↑ Cable L W Judas Iscariot, Betrayer or Enabler, Fact or Fiction? in Sceptics Corner essay collection

- ↑ Q 22:28,30 By Paul Hoffmann, Stefan H. Brandenburger, Christoph Heil, Ulrike Brauner, International Q Project, Thomas.

- ↑ Jesus, apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium By Bart D. Ehrman.

- ↑ Hyam Maccoby, Antisemitism And Modernity, Routledge 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Timeline of early Christianity at National Geographic

- ↑ Judas 'helped Jesus save mankind' BBC News, 7 May 2006 (following National Geographic publication)

- ↑ Cockburn A The Gospel of Judas National Geographic (USA) May 2006

- ↑ Cockburn A at page 3

- ↑ Deconick A D Gospel Truth New York Times 1 December 2007

- ↑ Statement from National Geographic in Response to April DeConick's New York Times Op-Ed "Gospel Truth"

- ↑ Acocella J Betrayal: Should we hate Judas Iscariot? The New Yorker 3 August 2009

- ↑ pelo de Judas ("Judas hair") in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

- ↑ Page 314 of article Red Hair from Bentley's Miscellany, July 1851. The eclectic magazine of foreign literature, science, and art, Volumen 2; Volumen 23, Leavitt, Trow, & Co., 1851.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Page 256 of Letters from Spain, Joseph Blanco White, H. Colburn, 1825.

- ↑ Judas colour in page 473 of A glossary: or, Collection of words, phrases, names, and allusions to customs, proverbs, etc., which have been thought to require illustration, in the words of English authors, particularly Shakespeare, and his contemporaries, Volumen 1. Robert Nares, James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, Thomas Wright. J.R. Smith, 1859

- ↑ http://www.sybertooth.com/blaylock/lastcoin.htm

- ↑ http://metal-archives.com/

External links

- The Prophecy of Judas in Psalm 41 Video

- Judas Iscariot: Catholic Encyclopedia article published 1910

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Judas Iscariot

- "Death and Retribution: Medieval Visions of the End of Judas the Traitor" - 1997 lecture by Dr Otfried Lieberknecht

- Gospel Truth

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||